MacIntyre as a Touchstone

Tradition, practice, and community in history and eternity

Welcome to The Blackthorn Hedge. This letter discusses the moral philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre as one of my ideological touchstones, the second in a small series planned in “Laying the Hedge: Arc 1” and begun with a letter on Pierre Bourdieu three weeks ago. MacIntyre is particularly known for his work on tradition, practice, and moral community, and so this is also intended to complement my several prior letters on tradition and solidarity.

As with Bourdieu, “touchstone” here does not imply “unquestioned authority figure” – I consistently respect Bourdieu and MacIntyre but not without disagreements.

As always, I welcome all respectful comments, messages, and other engagement.

In my letters here at The Blackthorn Hedge, no topic has been more important to me in these early days than “tradition,” understood broadly as “what is handed down.“

I’ve had five letters directly titled or subtitled by some theme on tradition: “Differentiating Traditions,” “Ecology of Tradition,” “The Tissues of Tradition,” “Digesting Tradition,” and most recently “Grounding Tradition.” In the others, I’ve also often been concerned with matters of tradition, as in the three letters so far on background to John Ganz’s contemporary fascism thesis: these depended most on Weberian and Frankfurt School tradition, Gramscian tradition, and Hegelian tradition, respectively; in reflecting on each of those, I also brought in other intellectual traditions by contrast, such as Galbraithian economics, Polybius’s political anacyclosis, and Smithian ethics.

The specific reason for this is that I am trying to put down roots for a hedge, to create a distinctive sense of a defensible intellectual place and, eventually, a community with a distinctive solidarity. I intend “tradition” to be a central organizing concept for persuasive communication within this space and community, as it emerges, and I intend to hold ground against alternatives like “memes” and “beliefs.” “Tradition” implicitly sets the standards for community diversity and commonality deep, whereas “memes” and “beliefs” lend themselves to organizing shallower differences and similarities.

Of all of my references for thinking about tradition, from the secular, progressive materialistic “scientific research traditions” of Larry Laudan’s Progress and Its Problems to the esoteric, mystical Christian and Hermetic traditions of Valentin Tomberg’s Meditations on the Tarot through the conservative, established artistic tradition of T. S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” the most consistent center of gravity for me has been Alasdair MacIntyre’s work in moral philosophy.

This is not because I have simply agreed with MacIntyre more than the other authors. It is instead because he is most consistently focused on what I think are the heaviest, most fundamental problems of tradition: issues of life and death dependence on trust in others, issues of subjectivity and objectivity in the grips of strong emotion and collective enthusiasm, and issues of how communities with shared practices serve as grounds of rational deliberation, for instance.

In my last touchstone letter, I admired Pierre Bourdieu as an intricate thinker, certainly capable of depth and weight but most notable for his precision. MacIntyre I admire most as a weighty thinker, with his own intricacy and precision to be sure but most notable for his gravity.

Accordingly, MacIntyre is much less of an enigma than Bourdieu. Whereas Bourdieu “has been authoritatively placed in all the major theoretical traditions” from Marxian to Weberian to Nietzschean to Structuralist,1 MacIntyre is unambiguous. He’s a former Marxist, Catholic Christian, and an Aristotelian virtue ethicist: a champion of St. Thomas Aquinas. His loyalties were clear: he was a traditionalist critic of liberalism willing to work with non-liberal leftists. This makes him an entirely different challenge to write about than Bourdieu. The challenges in reading them are as different as the challenges in gymnastics and deadlifting.

Since MacIntyre was not embroiled in the same sort of intricate, many-front intellectual battles of identity that Bourdieu was, there’s less of a need to discuss all the ways his work has been received. It’s more feasible to simply start reading him, and I highly recommend it! I recommend beginning with Dependent Rational Animals, and I’ll begin the next section with its opening paragraphs.

If anyone reading this would like to read that book and write something about it, I’m sure to subscribe to your Substack and become interested in your goals if and when you do. Please ping me to be sure I see it.

MacIntyre made his name with After Virtue in 1981 and it has remained the primary basis for his fame as a moral philosopher, but 1999’s Dependent Rational Animals is a softer and more approachable introduction to his thinking. It is an adaptation of a series of invited lectures. This is how it begins:

We human beings are vulnerable to many kinds of affliction and most of us are at some time afflicted by serious ills. How we cope is only in small part up to us. It is most often to others that we owe our survival, let alone our flourishing, as we encounter bodily illness and injury, inadequate nutrition, mental defect and disturbance, and human aggression and neglect. This dependence on particular others for protection and sustenance is most obvious in early childhood and old age. But between these first and last stages our lives are characteristically marked by longer or shorter periods of injury, illness, or other disablement and some among us are disabled for their entire lives.

These two related sets of facts, those concerning our vulnerabilities and afflictions and those concerning the extent of our dependence on particular others are so evidently of singular importance that it might seem no account of the human condition whose authors hoped to achieve credibility could avoid giving them a central place. Yet the history of Western moral philosophy suggests otherwise. From Plato to Moore and since there are usually, with some rare exceptions, only passing references to human vulnerability and affliction and to the connections between them and our dependence on others. Some of the facts of human limitation and our consequent need of cooperation with others are more generally acknowledged, but for the most part only then put on one side. And when the ill, the injured and the otherwise disabled are presented in the pages of moral philosophy books, it is almost always exclusively as possible subjects of benevolence by moral agents who are themselves presented as though they were continuously rational, healthy and untroubled. So we are invited, when we do think of disability, to think of “the disabled” as “them,” as other than “us,” as a separate class, not as ourselves as we have been, sometimes are now and may well be in the future. (Dependent Rational Animals (1999), pp. 1–2)

The first thing to note is how dated this is! 25 years have changed moral philosophy, and the discussions of disability have changed more than most. Academic and popular discussions are both different from what they were in the late 90s, especially since the 2010s. MacIntyre helped make that happen. One could argue this is an early example of the “woke right,” a category I find silly, but it’s certainly a good example of both left and right identifying similar weaknesses in the ideology of the establishment center.

The second is that it’s sweeping and contentious. That’s MacIntyre’s style. The style is a challenge for many readers, and it’s part of what makes him a good touchstone – people’s opinions of him quickly reveal a lot about how they think about historical judgment and where they accept rhetorical simplification or not. Is it enough for a reader that he often says “almost always” or otherwise hedges the sweeping statements? Or does it come across as just abuse of technicalities to get away with sweeping over his own ignorance?

For me, the expressions of uncertainty matter. My background in physics was strongest in statistical mechanics, and so I’m very confident with statistical language like “on average,” “almost always,” “typically,” and “characteristically.” As long as a writer uses them consistently, I’ll figure out the technical details and evaluate the arguments accordingly. It might be tricky to figure out if they use “often” to mean “enough that it’s not surprising” or “most of the time” or something else, but it’s rarely impossible.

What matters more is whether I can go back and check the history myself. This is difficult with MacIntyre because he makes precise, original claims about wide-sweep history without (1) sharing his background sources for the sweep or (2) sharing the exact criteria for his precise claims. This is one of the things that makes reading him a difficult proposition. Whereas Bourdieu is difficult at the sentence-parsing level, he’s more transparent than MacIntyre about his data and sourcing. With MacIntyre, following the arguments requires long immersion in the philosophical tradition. If there’s some claim you don’t understand, you may need a year to check that claim properly. It’s heavy lifting.

The next two paragraphs make a case in point:

Adam Smith provides us with an example. While discussing what it is that makes the “pleasures of wealth and greatness… strike the imagination as something grand and beautiful,” he remarks that “in the languor of disease and the weariness of old age” we cease to be so impressed, for we then take note of the fact that the acquisition of wealth and greatness leaves the possessors “always as much, and sometimes more exposed than before, to anxiety, to fear and sorrow, to diseases, to danger and to death” (The Theory of Moral Sentiments IV, chapter I). But to allow our attention to dwell on this is, on Smith’s view, misguided.

To do so is to embrace a “splenetic philosophy,” the effect of “sickness or low spirits” upon an imagination “which in pain and sorrow seems to be confined,” so that we are no longer “charmed with the beauty of that accommodation which reigns in the palaces and economy of the great…” The imagination of those “in better health or in better humor” fosters what may, Smith concedes, be no more than seductive illusions about the pleasures of wealth and greatness, but they are economically beneficial illusions. “It is this deception which rouses and keeps in continual motion the industry of mankind.” So even one as perceptive as Smith, when he does pause to recognize the perspectives of ill health and old age, finds reason to put them on one side. And in so doing Smith speaks for moral philosophy in general. (Dependent Rational Animals (1999), p. 2)

This puts a heavy finger on a painful vulnerability. I’ve read the full Theory of Moral Sentiments and come to my own conclusions about whether this is fair, and my conclusion was a horrible, reluctant, technical… yes. Smith is not simply endorsing these illusions on economic grounds here, that would be an unfair oversimplification of his more nuanced, nearly-esoteric critique of the aristocracy and their control of demand through mimesis in the pre-industrial economy – but it is still fair to say that he is “putting the perspectives of ill health and old age to one side.”

This is a perfect example of what frustrates liberal philosophers about MacIntyre. He has made a technical point here that is correct, but with terrible, incorrect implications for someone less familiar with the background: Smith comes off as a man who simply sacrifices truth for economic growth at the expense of the ill and aged!

And yet to explain exactly why that implication is incorrect without contradicting the technically correct point requires going into the specific claims Smith is indeed making – claims about how economic activity is mechanistically driven by systematic elite deception that relies on the social erasure of the ill, aged, and “splenetic.” Few liberals of the 90s liked to teach this “woke Adam Smith,” or if they did they liked to keep it discreet.

In implication, the liberal ideologists of the 90s were the ones sacrificing truth for economic growth at the expense of the ill and aged by misrepresenting Smith in their own rhetoric. They couldn’t save Smith without giving themselves up. Happily, times have now changed and I see much more of this truer Adam Smith in liberal teaching, to their credit.2

This is heavy lifting, as I said. There are high stakes and high emotions and it might take a few hundred pages of reading to check a key sentence. Unless you trust me or an LLM to do it for you, I suppose… but then we’re back to those thorny issues of dependence again, right where MacIntyre wants us.

In any case, you don’t have to check every one of these historical claims as you read Dependent Rational Animals. You can read it impressionistically and just take away whichever arguments seem clean and transparent given the background that you have. It’s a book that rewards multiple readings, and the first can skim the surface.

It might come as no surprise to learn that MacIntyre made his first impression on me at a low point in my life. I was recommended After Virtue in graduate school by a Christian historian friend after a bad breakup in which I was at fault. Terrible fault. I won’t get into it now, but suffice to say I needed a moral wake up call.

I’d been raised with a mishmash of secular ideologies, mostly Florida libertarian, 19th century European liberal, and Californian technocratic. Atlas Shrugged was often lying around at home and I read it young; I even won some money in one of the Objectivist essay contests as a teenager – I immediately spent it on my own literary prize for the best criticism of my high school and the winner was an amazing Inferno parody with the correct rhyme and meter. The best word for me would have been “cynical.” Cynical but still judgmental, especially about honesty.

The cynicism tended to compound itself. I discovered Nietzsche from Rand and then had new ways to find fault with everything around me. A high school girlfriend was deeply into Cruel Intentions and Dangerous Liaisons and, terrifyingly and brutally, not just as theory but also as her practice. I felt my first classes in undergrad philosophy to be uninspiring social conformity games and chose to pursue science instead. I found the sciences were made political and dishonest by grants gamesmanship. For most of this time I was ideologically rebellious but I became disillusioned with the rebels as well.

I had also been in a lot of pain and had a lot of nightmares. I was often ill. Doctors usually didn’t find anything wrong with me and called it “idiopathic” or sometimes they did but there was nothing to do about it – I kept getting strep even though that wasn’t supposed to happen, for instance. In high school I began to get debilitating headaches, and in my first years of undergrad they were often bad enough I wouldn’t leave my room or talk to anyone for full days. In retrospect they were cluster headaches.

In the middle of undergrad, I closed off from people and focused more and more on work and a long term relationship. I became focused on health and regular habits; I read Camus and “imagined Sisyphus happy.” I tried to depend on people less and less and mechanical systems more and more. My pain receded, but my fears, disillusionment, and self-isolation did not. I tried to get some help from therapists but there wasn’t apparently much to do.

Today, the therapists in the same school offices would probably recognize the underlying trauma and have better tools for handling it than they did fifteen years ago, but I wasn’t going to get that part of the story for many years yet. Instead, I got lonelier and worse as a person and made that terrible botched breakup in grad school. In the pathetic aftermath, I was lucky a kind Christian recognized the misery of my misanthropic, self-judgmental cynicism and gave me After Virtue as an antidote.

This isn’t too unusual as a story for someone who deeply appreciates MacIntyre, I’ve found. A lot of us are men who can power through pain most days but also understand illness from the inside at length, or who cared immensely about truth but couldn’t find any bottom for cynicism in secular ideology. A fair number of us have awful shames and regrets from those periods of our lives. The friend who recommended it to me certainly had the shames and regrets, the pain, and the former cynicism.

This is another aspect of the gravity of MacIntyre’s work. I’m not sure what pain he experienced himself, but when he makes his sweeping statements about pain and shame, it rings true to many men with heavy firsthand experiences. When he discusses the risks of seductive illusions, he seems to know very well what he’s talking about. He’s one of very few writers who I find can consistently meet Nietzsche and Dostoevsky on these levels, and who can speak with comparable insight and apparent experience.

As with Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, then, MacIntyre is a good weight reference as well as a good touchstone. From how a friend reads him, I can often get a fair sense of what moral difficulties they’ve been through.

There are dangers to reading After Virtue. It can be strong medicine. It begins with a vivid thought experiment to convey just how different MacIntyre’s perspective on moral philosophy is compared to most of his contemporaries:

Imagine that the natural sciences were to suffer the effects of a catastrophe. A series of environmental disasters are blamed by the general public on the scientists. Widespread riots occur, laboratories are burnt down, physicists are lynched, books and instruments are destroyed. Finally a Know-Nothing political movement takes power and successfully abolishes science teaching in schools and universities, imprisoning and executing the remaining scientists. Later still there is a reaction against this destructive movement and enlightened people seek to revive science, although they have largely forgotten what it was. But all they possess are fragments: a knowledge of experiments detached from any knowledge of the theoretical context which gave them significance; parts of theories unrelated either to the other bits and pieces of theory which they possess or to experiment; instruments whose use has been forgotten; half-chapters from books, single pages from articles, not always fully legible because torn and charred. Nonetheless all these fragments are reembodied in a set of practices which go under the revived names of physics, chemistry, and biology. Adults argue with each other about the respective merits of relativity theory, evolutionary theory, and phlogiston theory, although they possess only a very partial knowledge of each. Children learn by heart the surviving portions of the periodic table and recite as incantations some of the theorems of Euclid. Nobody, or almost nobody, realizes what they are doing is not natural science in any proper sense at all. For everything that they do and say conforms to certain canons of consistency and coherence and those contexts which would be needed to make sense of what they are doing have been lost, perhaps irretrievably. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), p. 1)

The thought experiment builds further, and then MacIntyre explains:

What is the point of constructing this imaginary world inhabited by fictitious pseudo-scientists and real, genuine philosophy? The hypothesis which I wish to advance is that in the actual world which we inhabit the language of morality is in the same state of grave disorder as the language of natural science in the imaginary world I described. What we possess, if this view is true, are the fragments of a conceptual scheme, parts which now lack those contexts from which their significance derived. We possess indeed simulacra of morality, we continue to use many of the key expressions. But we have – very largely, if not entirely – lost our comprehension, both theoretical and practical, of morality. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), p. 2)

In my opinion, the book delivered on substantiating that hypothesis. Ever since, I have lived as if a catastrophe of the magnitude of that speculative thought experiment had in fact occurred in recent history. It’s been impossible to listen to most everyday use of moral language without noticing the incoherences MacIntyre highlights.

I have also found reasons to believe that similar catastrophe has in fact happened in the sciences at least once before, via Lucio Russo’s often dry but excellent The Forgotten Revolution. MacIntyre’s description of the aftermath in this early section is eerily accurate to Russo’s description of post-Hellenistic history.

The possibility that modern moral language has lost its coherence has clear reactionary implications, and after reading MacIntyre I did spend some time growing more reactionary, to the point of joining in reactionary politics that brought me to Silicon Valley. However, it’s not necessarily or simply reactionary, and MacIntyre closes the opening chapter with a message to radical readers as well:

the modern radical is as confident in the moral expression of his stances and consequently in the assertive uses of the rhetoric of morality as any conservative has ever been. Whatever else he denounces in our culture he is certain that it still possesses the moral resources which he requires in order to denounce it. Everything else may be, in his eyes, in disorder; but the language of morality is in order, just as it is. That he too may be being betrayed by the very language he uses is not a thought available to him. It is the aim of this book to make that thought available to radicals, liberals, and conservatives alike. I cannot however expect to make it palatable; for if it is true, we are all already in a state so disastrous that there are no large remedies for it.

Do not however suppose that the the conclusion to be drawn will turn out to be one of despair… [] if we are indeed in as bad a state as I take us to be, pessimism too will turn out to be one more cultural luxury that we shall have to dispense with in order to survive in these hard times. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), pp. 4–5)

Since 1981, when this was published, this thought that a radical may be “betrayed by the very language he uses” has become widely available to the point of becoming commonplace. It’s often attributed to Lacan-influenced and Foucault-influenced critical theorists instead, today.

Something all of these theorists have in common is an attention to the embodiment of language, a preoccupation also shared by Bourdieu. MacIntyre is particularly attentive to the role of cooperative collectivity and community in this embodiment, but without driving out the place for religion.

in much of the ancient and medieval worlds, as in many other premodern societies, the individual is identified and constituted in and through certain of his or her roles, those roles which bind the individual to the communities in and through which alone specifically human goals are to be attained; I confront the world as a member of this family, this household, this clan, this tribe, this city, this nation, this kingdom. There is no ‘I’ apart from these. To this it may be replied: what about my immortal soul? Surely in the eyes of God I am an individual, prior to and apart from my roles. This rejoinder embodies a misconception, which in part arises from confusion between the Platonic notion of the soul and that of Catholic Christianity. For the Platonist, as later for the Cartesian, the soul, preceding all bodily and social existence, must indeed possess an identity prior to all social roles; but for the Catholic Christian, as earlier for the Aristotelian, the body and the soul are not two linked substances. I am my body and my body is social, born to those parents in this community with a specific social identity. What does make a difference for the Catholic Christian is that I, whatever earthly community I may belong to, am also held to be a member of a heavenly, eternal community in which I also have a role, a community represented on earth by the church. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), pp. 172)

I can’t do justice to the entire philosophy with short excerpts, but I hope this gives a sense of the revealing debates and conversations this book can start.

On the particular issue of “betrayal by moral language” and on the moral dignity of the disabled and on several others, MacIntyre makes an excellent test case for seeing if a reactionary can listen to and appreciate radical thought or a radical can appreciate reactionary thought.

Within After Virtue itself (and not only in After Virtue), MacIntyre mixes what are usually thought of as radical and reactionary claims close to one another. For example, he can be quite complimentary to Marx and Nietzsche at the same time he is sharply critical.

On Marx, the prologue to the third edition of After Virtue states clearly that

although After Virtue was written in part out of a recognition of those moral inadequacies of Marxism which its twentieth-century history had disclosed, I was and remain deeply indebted to Marx’s critique of the economic, social, and cultural order of capitalism and to the development of that critique by later Marxists. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), p. xvi)

This is simply complimentary, and that challenges many conservative or reactionary readers immediately. His final word on Marxism in the last chapter of the original book is this:

I [] not only take it that Marxism is exhausted as a political tradition, a claim borne out by the almost indefinitely numerous and conflicting range of political allegiances which now carry Marxist banners – this does not at all imply that Marxism is not still one of the richest sources of ideas about modern society – but I believe this exhaustion is shared by every other political tradition within our culture. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), p. 262)

This combines decisive criticism and high respect in one line. It spoke especially clearly for me because I had already been listening to the Marxist Platypus society discuss the exhaustion of Marxism as a political tradition among one another and with other Marxists for some time before reading this line. They showed me many Marxists were capable of hearing this sort of blunt criticism and that some would go so far as to agree. Being willing to hear it has become an important test of good faith for me, and I use a handful of other criticisms of Marxism from MacIntyre similarly.

My personal background had been much more Nietzschean radical than Marxist radical before reading MacIntyre, so I was personally sensitive to his choices of criticism and admiration for Nietzsche. I still think of Nietzsche as a member of my “heavenly community”3 in some sense to this day, though he’s an odd neighbor to have in eternity.

This is a fairly representative example of what MacIntyre has to say on Nietzsche:

For it was Nietzsche’s historic achievement to understand more clearly than any other philosopher – certainly more clearly than his counterparts in Anglo-Saxon emotivism and continental existentialism – not only that what purported to be appeals to objectivity were in fact expressions of subjective will, but also the nature of the problems that this posed for moral philosophy. It is true that Nietzsche, as I shall later argue, illegitimately generalized from the condition of moral judgment in his own day to the nature of morality as such; and I have already said justifiably harsh words about Nietzsche’s construction of that at once absurd and dangerous fantasy, the Übermensch. But it is worth noting how even that construction began from a genuine insight. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), p. 113)

This should be extremely easy for a Nietzschean to hear and engage with, in my opinion, regardless of agreement. It’s less inflammatory than most of what Nietzsche wrote without being so milquetoast to be offensive. It’s also likely to be something a reactionary can hear and engage with. Giving Nietzsche credit for accurate critical insight into something else that deserves criticism should be possible even for Nietzsche’s fierce opponents.

This nearby quote is another interesting test:

In another way, too, Nietzsche is the moral philosopher of the present age. For I have already argued that the present age is in its presentation of itself to itself dominantly Weberian; and I have also noticed that Nietzsche’s central thesis was presupposed by Weber’s central categories of thought. Hence Nietzsche’s prophetic irrationalism – irrationalism because Nietzsche’s problems remain unsolved and his solutions defy reason – remains immanent in the Weberian managerial forms of our culture. Whenever those immersed in the bureaucratic culture of the age try to think their way through to the moral foundations of what they are and what they do, they will discover suppressed Nietzschean premises. And consequently it is possible to predict with confidence that in the apparently quite unlikely context of bureaucratically managed modern societies there will periodically emerge social movements informed by just that kind of prophetic irrationalism of which Nietzsche’s thought is the ancestor. (After Virtue, 3rd ed. (2007), p. 114)

On the one hand, it’s superficially very high praise to be called “the moral philosopher of the present age”; on the other, it’s meant as a criticism of the age. It’s like being credited with the world’s most important lab leak.

There are other good candidates for touchstones like MacIntyre here. I’ve sometimes used Edmund Burke, though since reading about his contemporary history and reading critiques like John Thelwall’s I’ve become too personally confused about what to make of Burke as a politician to continue that. I’ve also sometimes used Isaiah Berlin, though since reading Hiruta’s Hannah Arendt and Isaiah Berlin I’ve decided not to do that again in public until conflicts over Zionism cool down again (if they do). For now, MacIntyre is my favorite choice.

None of this goes to say that I take admiration of MacIntyre as a necessarily good sign or distaste as a necessarily bad sign.

There’s the infamous case of the conservative Rod Dreher’s book The Benedict Option, which was inspired by After Virtue’s final line – “we are waiting not for Godot but for a another – doubtless very different – St. Benedict.” MacIntyre wanted nothing to do with it and considered Dreher to have missed the point, even as Dreher seemed to appreciate After Virtue. I’m happy to make similar judgments.

On the other hand, there are acid critics of MacIntyre’s work who I respect even when I think they’re missing some of the points. Particularly among liberals, I expect some of MacIntyre’s sweeping statements about English moral traditions to cross lines they won’t accept; among left radicals, I consider his austerity4 and his direct advocacies of authority to be respectable grounds for dismissing him. For an excellent example of a liberal making acid criticisms, see Martha Nussbaum’s review of Whose Justice? Which Rationality?. That’s a book that I personally learned a lot from. It’s MacIntyre’s closest to what I’ve been writing about tradition and solidarity here at The Blackthorn Hedge. Nonetheless, I respect her criticism there and I respect her other philosophical work; I think of her The Cosmopolitan Tradition often when writing my letters, as well.

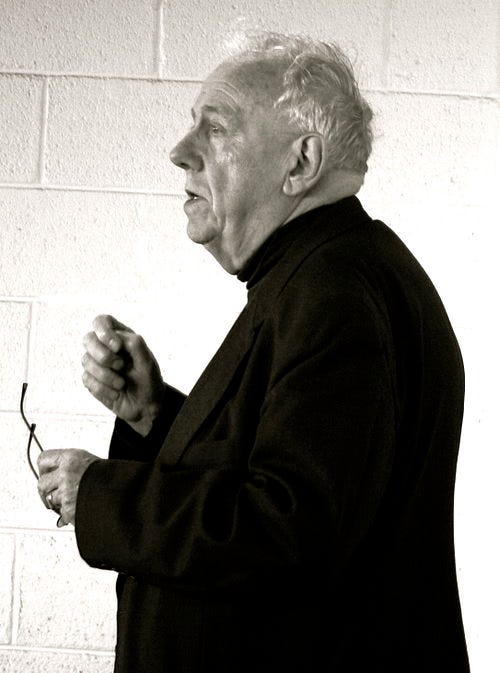

Alasdair MacIntyre passed away only recently, on May 21 of this year. By that time I had decided to start this Substack, but I still worried that I was choosing unwisely and I was unsure of some of my plans for beginning.

One factor that confirmed for me that I should go ahead was the many warm remembrances and tributes to MacIntyre here after he passed. A few:

The most unexpected to me was from John Ganz,

This past week saw the death of philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, author of After Virtue (1981), one of the great works of 20th-century moral philosophy. MacIntyre began as a Marxist but converted to Catholicism and dedicated himself to the recovery of the tradition of virtue ethics that began in the classical world, was first articulated by Aristotle, and then developed by Saint Thomas Aquinas in the Middle Ages. I’ve always been fascinated with MacIntyre and have read After Virtue a few times (although, perhaps, never quite cover-to-cover—the ideas are breathtaking, the writing you have to wade through to parse them, somewhat less so.) When I told a philosophy major friend how much I admired MacIntyre, he replied, “Well, that makes sense since you are both cranky Aristotelians,” which I took as a great compliment. ( “Ehud Olmert on Gaza; reading After Virtue after bureaucracy; A Postscript”)

Seeing that was welcome, and was crucial for my decision to spend serious time on his thinking about contemporary fascism. Being critical of the prose makes perfect sense if one’s standards are set by Trilling and Hazlitt, like Ganz’s are. Taking “cranky Aristotelian” as a compliment fit other character details into place and gave me confidence that starting into Reactionary Modernism would be well worth my time. I haven’t regretted the choice.

I look forward to learning more about others through their engagements with MacIntyre here. I hope some one or two of you do take up Dependent Rational Animals and read the whole thing. I’ll continue to draw on his work in the letters I write, directly and indirectly.

Thank you for reading. As always, I welcome all respectful comments, messages, and other engagement.

See prior letter on Bourdieu.

Particularly in Nussbaum, see below.

Recall the p. 172 quote.

For instance the “pessimism is a luxury we can’t afford” above.

As someone interested in reading MacIntyre, I really appreciated this. I didn't know anything about him but after his death saw a few writers I liked mentioning him, and then I kept seeing his name pop up and maybe I read an article by him as well, I can't quite remember. But I had the feeling that his ideas would resonate a lot with me, and this confirms it. I will try to pick up one of his books.

I don't think I realize what MacIntyre has done to the field of ethics just because I'm a bit younger. Im about halfway through after virtue and his insights are incredible and go beyond just restarting Aristotle. Great scholar and cultural critic.