So far at The Blackthorn Hedge, I have posted a variety of essays on topics meant to define a space for some freedom and integrity in my online writing. I’m looking to establish standing to hold this ground and participate in contentious conversations as myself rather than as an assimilated partisan of an existing social movement. I don’t currently find myself well-represented by any movement that I’m aware of, even or especially the ones that think of themselves as uncontroversial and welcoming of everyone.

But while I’m not well-represented by movements, I am a representative of some traditions. This is an occupational hazard of anyone who reads a lot of old nonfiction: it’s easy to become committed to “dead” or idiosyncratic positions and thus out of step with contemporary collective conversations. To represent traditions without movements.

Tradition is a tricky word, but basically it just means “something handed down” and that’s how I often use it: at its most basic, “tradition is just everything received from others.” Something as simple as a single teacher’s way of teaching multiplication counts: everyone who learns it that way now has that as a tradition of how to multiply. “Someone’s tradition” in this sense is everything they have had handed down to them or everything they hand down. These uses of “tradition” make it an indefinite plural like “water.”

“Traditions” above meant something different, since it’s a definite plural. However, defining “a tradition” for the plural “traditions” is frustratingly tricky. It’s circularly recursive: there can be said to be different traditions for using the word tradition. This essay itself will be an act of handing down a tradition of how to use “a tradition.” I won’t go deeper into all this here, but I can recommend Lee Braver’s sharp Groundless Grounds to those who are interested. Instead, I’ll name and contrast a couple of traditional ways of using “a tradition” to introduce my own (and yes, this contrastive method is also tradition).

What I have to say here is finicky, abstract, and too often idiosyncratic to me, so I understand I will have asked a lot of those of my readers who finish this letter. I think it is warranted, however: I find this important precision for speaking clearly about tradition, and I think that today it is very important to develop and spread better ways to speak clearly about it.

For the last few hundred years, conflicts between tradition and innovation have been central themes in popular debate but all along there have also been insightful voices (such as Larry Laudan, T. S. Eliot, and Alasdair MacIntyre) pointing out that innovation is done within and by traditions, not simply against them. Today, I believe that these issues are more important than ever as traditions of artistic and technological disruption clash against traditions of domestic continuity. This seems to be crucial for understanding today’s ethnic conflict crises, sexual conflict crises, and generational conflict crises.

I can state this belief I hold about present crises flatly up front, without explanation. It might even have a strong rhetorical effect on people who assume they already know what I mean! To explain it properly, however, first I would need to explain better what I mean by “traditions” and how they can come into conflict. Those preliminary explanations are all I will do in this letter. The explanatory concepts also have many other gentler uses, for instance in discussing literary genres and fashions, establishing standards for rationality and irrationality with friends, or cultivating everyday imagination. I will leave any further writing connecting them to contemporary crises for another time.

Please skip this letter if you’re not interested: this is a special interest piece. If you are interested, let’s go ahead and discuss tradition in more detail.

Phyletic and Moietic Tradition

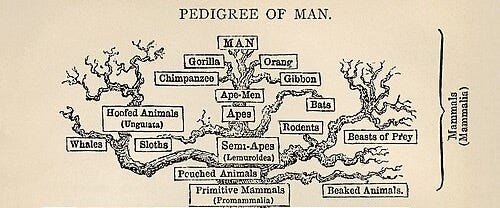

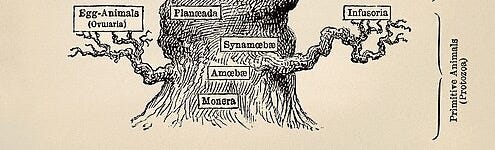

First, among traditions there are what one might informally call “the big traditions.” Big philosophical traditions include “Platonism” and “Neoplatonism,” “Aristotelianism”, “Augustinian Christian philosophy,” “Thomism,” “ordinary language philosophy,” and “analytic philosophy.” In literature, there are traditions like “domestic realism” and “magical realism”, “Shakespearian drama” and “Pynchonian picaresque”, “Russian literature” and “English literature.” These are like species, genera, or phyla from biology, and they have a similar sort of branching “family tree” structure to them, where the big traditions also include nested sub-traditions of similar kinds and newer traditions can sometimes be understood as combinations of older traditions.

I call these all phyletic traditions from their relationship to phyla in biology. Their nesting and hybridization histories are a phylogeny. In another tradition established by Richard Dawkins and Susan Blackmore these correspond to “memeplexes.”

Characterizing phyletic traditions is tricky. Some people trace these traditions by their exemplary innovators, especially the ones named like “Aristotelianism” or “Thomism.” Others trace the traditions via the common patterns of communities of practitioners, such as “ordinary language philosophy” or “analytic philosophy.” Others are in between, as with “Augustinian Christian philosophy,” half named for St. Augustine and half for the community of Christians (themselves named for Christ). There are phyletic exemplar traditions, phyletic community traditions, and if someone wants to be mean, phyletic epigone traditions; there are also many more.

Sometimes the traditions are named from within and sometimes they are named by outsiders, even by opponents, like the Phoenicians never called themselves Phoenicians before the Greeks began to use that label.1

I recognize all these uses, and “phyletic tradition” covers them all.

Second, there is a complementary opposite kind of tradition that one might think of as “small traditions,” particular things handed down, like a particular detail of how to style one’s writing or an individually meaningful book. These might or might not correlate with any particular big phyletic traditions. Among books, for example, if they’re the core books of a phyletic tradition in philosophy, say Aristotle’s Categories, then they certainly will correlate with that tradition (in this case Aristotelianism), but if they’re widely readable popular entertainment books, say The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, they may not correlate with any specific philosophical tradition (there are phyletic traditions in entertainment, here dry English humor, that they do correlate with).

Since these are part-like or feature-like rather than species-like, I call them moietic traditions.2 They correspond to individual memes or clusters of memes rather than full memeplexes, in the Dawkins-Blackmore language. “Meme chromosomes” or “meme plasmids” are metaphors I’d try to use if I felt better about “memes” as an idea in the first place.

Moietic and phyletic traditions are mutually constitutive. Any abstract phyletic tradition, such as “Aristotelianism” or “English literature” as such, will always be instantiated in individuals as a composition of concrete moietic traditions: the results of particular philosophical training and reading that an Aristotelian went through, for instance, or the results of the particular literary experiences and practices that an English author has undertaken. Vice versa, abstract moietic traditions such as “an English book” or “a characteristic English style” cannot be abstracted in a communicable way except through concrete phyletic traditions: whether something will be thought of as an English book or an English style at all depends on prior integration into concrete phyletic traditions of recognition and criticism.

This is all self-consciously conceptualized in parallel to evolutionary biology because I am a firm believer that viable intellectual traditions require a cognitive grounding in material modes of production. Traditions of abstract thought about thinking simply are never profitable enough to stand on their own without cross-subsidy from simultaneous traditions of analogous concrete thought about material production that generates valuable material goods. Bioengineering, from biochemistry to directed evolution, is one of the most important and most profitable newly growing material modes of production of the last hundred years, and so it represents an important opportunity for grounding new intellectual tradition.

However, at the same time I am also intentionally rejecting the Dawkins-Blackmore language of “memes” and “memeplexes” with that same bioengineering basis. Like an increasing number of biologists, now recognized in major popular-audience books like Philip Ball’s How Life Works: A User’s Guide to the New Biology, I now reject the scientific framework in which “the selfish gene” is the central analytical unit of evolutionary biology. Genes are only one type of heritable material, and genes by themselves are not replicators: insofar as there are self-replicators in biology those would be whole cells or autocatalytic RNAs. Genes are replicated units: moieties. And they are not the only kind of replicated moiety; gene regulatory elements may be just as important and the polymerase and ribosome complexes are certainly as important. So “selfish moieties” would need to replace “selfish genes” but that would only expose further conceptual problems.

That, however, would become a digression. I don’t mean to get into the weeds here: this is my own clash with an opposing tradition, and I am presenting it now as a transition to discussing clashes.

Clashes of Traditions

The conflict between my way of discussing phyletic and moietic tradition and the “memes and memeplexes” way is an example of a few types of clash in itself.

First, the two moietic traditions of the particular vocabularies clash as practical substitutes for one another. They’re not mutually exclusive substitutes at the person-level (clearly I’m using both right now), but they are mutually exclusive in simple trains of thought: practically speaking, I’ll usually think about tradition in terms of just one or the other at a time; I only combine the two in more complex trains of thought contrasting them, like in this letter.

Second, the two moietic traditions clash as attentional substitutes for one another. The Blackmore-Dawkins writings on memes get more attention in general, but at the moment a reader is reading this, my “moietics and phyletics” is getting their attention rather than “memetics.” The audiences for this kind of work are not especially large or flex-time rich, so the attention is scarce and each substitution matters.

Third, my vocabulary also comes from a new phyletic tradition of thinking with premises that specifically contradict premises of the Dawkins-Blackmore approach. So now a Blackthorn phyletic tradition contradicts the Dawkins-Blackmore phyletic tradition. If the contradictions become widely believed, that could pressure the Dawkins-Blackmore tradition to evolve either to include refutations of the Blackthorn tradition’s contradictions of it, to robustly ignore the contradictions, or to reform to abandon the contradicted premises.

These clashes are not entirely destructive or zero-sum, of course.

For example, if the Dawkins-Blackmore phyletic tradition evolves to reform to abandon the premises my Blackthorn tradition contradicts, then it may do so by taking the contradictions as new moietic tradition for its own use. Depending on how the evolution proceeds, the new tradition may even become a recognized new hybrid of the two original phyletic traditions, something like “Dawkins-Blackmore-Blackthorn memetic theory.”

For another example, though attention for these vocabularies is scarce, it may be that they complement one another enough to increase overall attention to vocabulary of this kind. In this essay itself, I might be bridging a social gap between prior traditions of talking about tradition as tradition and talking about it in terms of memetics in such a way as to increase the attention “memetics” people pay to “tradition” people and vice versa, and in some cases bridges like these may even increase the attention paid to bridged areas more than the bridges themselves consume attention.

These first examples of clashes were each fairly clear and direct, but not all clashes will be.

Sometimes one moietic tradition doesn’t substitute for another but still inhibits the learning of the other, most obviously in cases like when someone reads a satire of a classic book before the classic. One can still read that classic afterwards, but it might be impossible to get the traditional effect of the traditional book. Satire is a particularly obvious example, but similar effects happen in all extended traditions where later moietic tradition in a phyletic tradition, say new geometry textbooks or a bold modernist novel like Joyce’s Ulysses, can recontextualize the earlier moietic traditions, say Euclid’s original Elements or Eliot’s classic Middlemarch, so thoroughly that the new tradition obscures meaning of the old. Pointing this out occasionally becomes an obsession for a philosopher like Nietzsche (with Greek tragedy) or Heidegger (with pre-Socratic philosophy).

Similarly, even when phyletic traditions do not directly contradict one another, they may promote social environments that are inhospitable to one another. In American short stories, the minimalist tradition exemplified by Hemingway and Carver often comes along with a macho sensibility that clashes with sensibilities encouraged by feminist political traditions even if they’re not the same kind of tradition, even if the stories are not simply contradictory to the politics, and even if excellent feminist appreciations and uses of Hemingway or Carver are possible.

This is a particularly clear example, but these can also be subtle. Recently “microaggression” became an iconic, somewhat scandalous term for describing particular alleged subtle social clashes between ethnic traditions. The word “microaggression” itself started to be considered a hostile moietic tradition in right wing phyletic traditions. These right wing traditions countered by naming it “woke” and thus attributing it to an opposing phyletic tradition, and in some senses that created “woke” as a phyletic tradition just like the Greeks once created “Phoenician.” There had been self-identified “woke” people before right wing opposition to “woke,” but the right wing opposition transformed the meaning significantly, to the point many people now deny “woke is a thing” altogether. All of these moves are on the table in a clash of traditions: creating combative moietic traditions, pejoratively labeling a new phyletic tradition, and denying the new tradition actually exists.

I will not pretend to present an exhaustive and complete typology of clashes of tradition here. That would become a textbook. Instead, I hope this has been enough to give some rough sense of the tangle of possibilities.

Applications

Each example up to now has been an analytical application of the concepts for tradition that I’ve introduced so far. I’ve given examples from philosophical tradition, literary tradition, political tradition, and scientific tradition. Two of the books on tradition that I recommended up front, Laudan’s Progress and Its Problems and MacIntyre’s Whose Justice? Which Rationality? are primarily about phyletic community traditions in scientific research and phyletic exemplar traditions in philosophy, respectively. While reading Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent”, I find many uses for both phyletic and moietic tradition in my understanding of that essay.

These analyses also have social and political uses, as so many intellectual analyses do. One of the social uses I have for this, for instance, is to solidify my boundary with the social traditions downstream of Richard Dawkins (i.e., have his books or quotes among their moietic traditions). If I can create narratives that consistently outcompete “meme” narratives in my local social ecology, then those narratives naturally push out attempts by various annoying phyletic traditions of scientism to use “meme” talk get a toehold in my local environment. Hopefully others who are similarly tired of those traditions of scientism may find this similarly useful.

While I haven’t talked about it yet, I also find all of this useful in conversation about influence: literary influence, political influence, cultural influence, etc. All tradition is influence, while not all influence is tradition. Influence in the form of tradition complements and competes with influence of other forms, but the relationships can go deep. One of the odd questions that comes up is whether it’s right to think of adversarial influence as traditional influence: if every generation, artists seek to overcome rivals in the prior generation, but the rivalry consistently teaches them the same skills each generation, did the prior generation “hand down” these skills in a “tradition of rivalry”? Personally, I think it does make sense to think of it that way.

I also didn’t talk about “genealogy” such as Nietzsche and Foucault are known for, but that implicitly looms over this letter as well. The most I want to say on that for now is that Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morals is hardly a genealogy at all, but at best a very coarse comparative morphology together with sketchy speculative phylogeny. I still find much to admire in the work, but the naturalistic metaphor of “genealogy” is grossly inapt and undermines Nietzsche’s otherwise genuinely naturalistic methodology. He had his reasons for letting rhetoric trump dialectic, but it has made a conceptual mess that deserves a cleanup. Implicitly, the concepts for tradition in this letter are contributions to that cleanup effort.

These are distant concerns for many of us, however, and so I’ll conclude by bringing it nearer: to Substack itself. The concepts have shaped my engagement here from the beginning and also my appreciation for what I’ve found here.

First of all, I admire how many writers here are self-consciously attentive to the traditions that they follow and promote. I have a lot to learn about the particular moves that they use to do what they do, but for instance:

(1)

has established his writing around an English literary tradition specifically for common readers and their tastes, and is therefore particularly attentive to how amateurs maintain relationships to phyletic professional traditions in literature and vice versa.(2)

maintains clarity and focus on a concise moietic canon of core works for a well-defined Lakatosian research program that makes simple, empirical predictions without fetishizing falsifiability. From the left, he nonetheless respected MacIntyre and he talks of his own work in terms of phyletic traditions it advances and opposes.(3)

constantly expands an already extensive moietic web of citations and references from contemporary empirical social sciences and systematic analytic philosophy to support his own creative iteration of a paradigm of cognitive behavior firmly in the phyletic tradition of functionalist, evolutionary, markets-and-incentives analysis. At the same time, he makes space for serious engagements with older concrete historical precedents such as Walter Lippmann’s work as a moietic tradition.Next, my favorite follows on Substack are consistently people with particularly clear senses of the traditions they are interested in and which small pieces fit where. Three good examples for my own interests have been

, especially for neoconservative and literary politics, (@inpursuitofwonder), especially for literary fantasy writing, and , especially for high modern and highly odd history and literature.If they take notice of an article, I’m very likely to get a lot out of reading it. Because they and the traditions they track and participate in organize work into complementary wholes, the rewards of reading them tend to compound: the more recommendations I follow, the more I get out of each recommendation — not just more from each next one, but also more from the past ones retroactively.

Last Thursday, I wrote something about what I am writing on Substack, “establishing a hedge that borders fields.” This letter is ending with some description of how I am reading and engaging: why I have chosen to border the fields that I have and how I benefit from those borders. I have private intellectual traditions I’m committed to that I’ll bring here gradually, like this one, and I’ll hope that they come to complement the existing ones well.

See Josephine Quinn’s excellent In Search of the Phoenicians, or for another set of similar examples, see James C. Scott’s writing about naming barbarian groups in Against the Grain.

Thanks for the mention!