Motte and Bailey; Hedge and Field

Fantasy and nature metaphor for making and defending spaces on the Internet

Trolls and Tropes

The public Internet is not a safe or simple place to talk. It is the most surveilled and contested communication medium yet made. Its connectivity makes it easy to cross social lines and easy to attack exposed communities, while also drawing communities to expose themselves for ease and opportunity, creating perfect conditions for culture war. For that reason, many of my favorite people mostly stay offline. They leave the Internet to the trolls.

Everyone knows the trolls, now, and how much they’ll burn for their lulz. There are also orcs who specialize in coarse, aggressive tribalism; there are also dry, dead, patient bodaks with death stares and curses for whoever might be having the wrong kinds of fun. The Internet is for everyone, not just the nice people.

If someone writes on the Internet, they’re well-advised to stick to anonymity, private spaces, and safe topics unless they’re ready — up front, off the bat — to take heat. If they are ready, then they might thrive in combat with the trolls, orcs, and undead. Even those most serious personal blows in the culture war, hit pieces in national newspapers, can be survived and turned into opportunities for greater notoriety and popularity.

It is possible to establish firm bases from which to repulse attacks, reputational castles and kingdoms, in the forms of author-moderated blog comment sections, assertive forum cultures, and archives full of ready-to-link rhetorical defenses. These castles can attract many followers who want protection for themselves, as well, so long as the costs and compromises of taking protection are not too high.

Now rather than drop that colorful trope language of trolls and orcs, castles and kingdoms as just a flowery, energetic introduction to a disenchanted discussion of Internet conflict and self-defense, instead I want to take tropes as my topic directly. Tropes like the troll and the “motte and bailey” aren’t accidental or inessential metaphors: they are actual symbols by which people cognitively process their conflicts. The actual cognitive patterns of online culture war bear many signs of being formed from fantasy and sci-fi games, movies, and novels.

These tropes are practical archetypes of interaction, a common layer of symbolism for people of ages 7 and up. On the Internet, you can’t always tell if you’re talking to a 7 year old or a 70 year old, but you can bet that they’ve seen a troll or imagined themselves in shining heavy armor. Those cognitive patterns people can assume as shared background are crucial for communication: they are the grounds for all possibilities of genuinely and effectively understanding one another. Philosophers I take seriously call them “the shared lifeworld.”

Lifeworlds for the Online

“Lifeworld” has German origins, as you might guess from the compound word form. It comes from “umwelt” in the study of animal behavior. This sort of lifeworld is a world as it appears to a living animal: what it can see and feel, what signals can have meaning for it. A fully colorblind person’s lifeworld does not contain color; a bird’s lifeworld often includes many more colors than ours. For some animals, these colors may have immediate felt meanings, especially in parental bonding and sexual attraction. An excellent book on animal senses and lifeworlds recently came out and stayed on bestseller lists for months: Ed Yong’s An Immense World.

Sharing lifeworlds is how animals become capable of communication and mutual understanding. Given shared fears of hawks or foxes, one bird’s call can signal a warning to others; given shared appetites for seeds or bugs, the calls can signal opportunities. The emergence of full-fledged languages from these simple communications is explored well in Abram’s The Spell of the Sensuous and a classic description of how human societies create richer shared lifeworlds via our languages and other social practices is Berger and Luckmann’s The Social Construction of Reality. I won’t summarize either here, but they’re both wonderful studies of how everyday life comes to have its meanings that we share with our families, friends, and colleagues.

It can be more difficult to find people online who share much common context, at first, but given time, online community can also offer comparable new mutual understandings. For some people these become more compelling than the understandings that were shared in person. When this seems good, we may call it “finding one’s people,” and when it seems dangerous, “radicalization.”

In either case the social implications are high stakes, and these stakes drive culture war. What parent can sit by while watching their child leave their shared lifeworld for questionable online alternatives? Especially when those might be self-harm groups or nihilistic political radicals? How can friends let friends leave them these ways — or not just leave, but rather pull them too, in these directions they may not trust?

All Substacks have some connections to these issues, and this one, The Blackthorn Hedge, cannot be an exception. By writing our pieces, we share elements of our own lifeworlds and we alter others’ lifeworlds. By writing regularly and attracting readers who form mutual recognitions of one another, we create new shared lifeworld altogether. This is one of the most rewarding aspects of writing and reading online, though it’s also why “the rich get richer” and a good publication needs to persist for a while to grow its audience: if it doesn’t become a stable feature of shared lifeworlds, it can’t create the same social satisfactions, and that takes time and scale.

With this Substack, I’m taking my time to get started. I am not declaring a movement with a manifesto or a new altcoin with a whitepaper. I’m first laying a base of material that can gradually create a shared, distinctive sense of place for readers. I’m also being mindful of conflict. My first few essays have included direct engagements with common online argument norms, with left/right political commitment, with feminism and anti-feminism, and with crypto politics because I don’t intend to let these issues lie and simply “go with the flow” or “stay under the radar.” Instead, I plan to make this space a tenacious hedge: “a brake and border for the more trampled fields of the open Internet,” per my current tagline. I am not interested in sharing only a thin, scared lifeworld with my audience. I will either share real conviction here or end the experiment.

This metaphor of the hedge, however, is not likely to become well-integrated shared symbolism for too many of my readers for some time yet. I’ll now do more work in that direction, by working from contrasts with more common fantasy tropes.

Caves and Castles; Trolls and Pests

One of the immediate strengths of the “troll” metaphor is that trolls live in dank, sad places. Calling someone a troll, you imply they belong in the dark. They should be kicked out of the shared lifeworld. “Go home, troll” means go be miserable. Similarly with orcs: orc tribes are stupid. “Go back to your tribe, orc” comes with vivid insulting implications not just for them but for their friends, too.

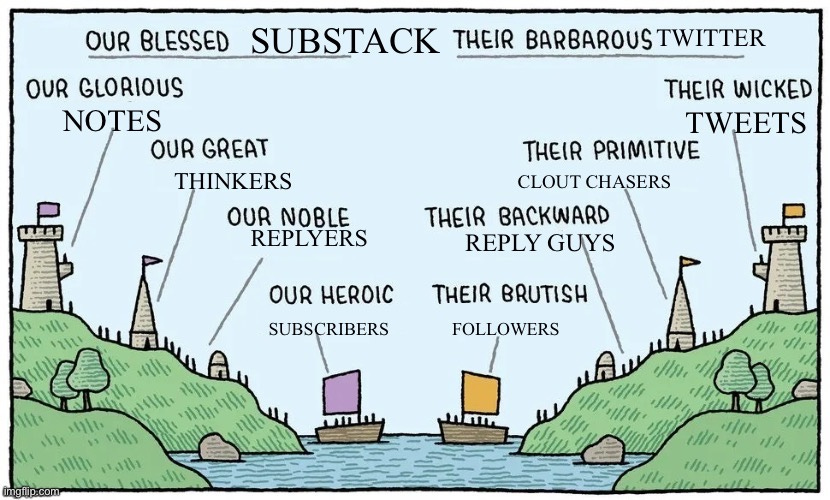

Fantasy metaphors are often like this: heavy handed and high contrast. They have bright lights and dark shadows. Since they exaggerate, they have an impact and a recoil. They may hit, but they’re also likely to be returned in kind. If two sides of social conflict get attached to opposite good vs. evil pretenses expressed in fantasy tropes, the situation can devolve rapidly. You get “our cute hobbits vs their filthy goblins”; “our cultured elves vs their brutish orcs”; “our wise magi vs their evil liches” — on both sides. It’s a meme.

So any “castle” to one social group is liable to be a “dungeon” to another, and there’s no use arguing which is right, because the point of these tropes is exactly that they’re just mapped onto personal friends and foes. They’re subjective. This effectively separates the groups’ lifeworlds. Happily, there’s also usually at least one neutral-coded extra alternative for each binary trope, and for castle and dungeon one option is “stronghold”. Switching to more neutral words may re-establish shared symbolism.

For lone trolls online, their homes may be tiny anonymous blogs or chat channels. When they gather and form strongholds, these are likely to be forums or Discords. They’re not likely to call themselves trolls, though it does happen. They’re more likely to have some positive story about themselves like that they’re pranksters, free speech activists, truth tellers, or superfans. What other communities think of as “nests of trolls” will typically think of themselves as just humor forums, free speech platforms, or edgy fandoms, and neither side will necessarily be wrong. The judgments are subjective. The lifeworlds aren’t shared.

For better and worse, if The Blackthorn Hedge grows, it’s likely to attract some regulars who others will think of as trolls and thus I’ll be judged as a shelterer of trolls, too. If so I won’t deny it, since it’s a subjective judgment, but it’s not how I’ll think of myself. In ecological terms, a natural alternative to “troll” is “pest.” Pests are simply animals in the way, animals going where someone thinks they don’t belong, and I’ll think of myself as having sheltered some pests.

This is normal for hedges. They’re good shelters for both wanted and unwanted animals. I’ll probably talk to the alleged pests. I’ll ask them to cut it out or to leave if the person making allegations has good points, but with no more sense of moral righteousness than I’d have relocating an unwelcome nest of mice.

Strongholds and Trees; Walls and Hedges

A few stones can’t make a wall, a few stakes don’t make a palisade, and similarly just a few posts rarely makes a defensible online territory. To make the simplest strongholds, it suffices to put down a ring wall of stakes. Online, planting down a set of posts about an interest that taken together create some sense of completeness and closure can do.

The posts of an online community stronghold need some sense of closure to create a shareable sense of a defensible interior in a space of ideas or identities. If they do, say by posting in a consistent style for every episode and every character of some single season of a beloved TV show or every major quest and NPC of a beloved RPG, then even very barebones wikis and blogs can create surprisingly durable zones for their online communities. Completeness or consistency can ground senses of solidity and authority that support community identities even when the content is informal or amateur.

More complex strongholds may have multiple closed structures, perhaps nested within one another or perhaps around multiple distinct but connected points of interest: the motte and bailey structure of an open public forum with a private patrons forum, for instance. “Motte and bailey” is more typically applied to a different situation in which communities have two complementary intellectual self-defense patterns: one weaker, used for the majority of talk, and one stronger, used when serious hostilities are encountered. An example would be when an amateur interest community’s members can usually feel safe talking informally about their interests using links and shorthand from an informal, non-scholarly wiki to support claims in conversation, but then retreat behind a community champion’s mastery of official sourcebook or game code references if and when outsiders start to challenge the simpler wiki summaries.

Larger communities may build many strongholds covering different points in idea space for themselves, each as complex as needs be, and they may network the strongholds into a larger territorial pattern.

However, this language of champions and strongholds is usually too bellicose and hierarchical for my intentions with my own writing and my own local society. I don’t like the effects of this thinking in implicit fantasy tropes that I see in communities like SF/F fandom sites or the old LessWrong. Talk of “tribalism” tends to inflame tribalism, and talk of sieges and walls tends to worsen siege mentalities and impulses to wall off outsiders. These shared symbols twist the shared lifeworld to overemphasize organized strategic conflict.

I do recognize the need for boundaries, but I prefer to start with less martial metaphors. For instance, while some online communities really do treat their leaders like feudal champions, others relate to them more like sheltering trees. A metaphorical swarm of ravens may caw in the comments sections of a blog like each of the posts are branches of a reliable old cherry tree, trusting the blog’s reputation and moderation to keep snakes and foxes on the ground and away. The conflicts emphasized there are less organized or strategic, more spontaneous and natural.

For other writing projects I might adopt this sort of tree-shaped approach myself, but for this one I’ve chosen the “hedge” metaphor because I don’t want any social life that settles around it to be reserved solely for the birds cawing above those stuck on the ground. I’m aiming to make space for the voles and other scamperers, too (that’s one reason why I picked my publication image).

The posts I’m planting down now to form an online space aren’t spiked logs or majestic oaks, but rather thorn trees. The lines aren’t so clean and the branches aren’t so high. I’ve distributed prickling points throughout the posts rather than each post making one deadly point. They’re more tangled pieces than I would write for business memos, movement bulletins, or academic journals. While this project is a hedge, I’m also hoping that I’ll be able to use it later to enclose a protected field or two for other simpler, straighter, less prickly kinds of writing.

In picking these details I didn’t make any full list of exactly what I was looking for and why, of course. I trusted my implicit intuition that some things were right and some were wrong and I trusted that I could figure out later the explicit reasons some symbols and styles seemed more apt than others.

That’s how the implicit lifeworld usually works. When making friends, first you may find people you click with, and then later you may find out how much you have in common as your initial small talk rapport matures into real friendship. With online spaces it’s the same: first people notice they like the feeling of the space, then later they might find words to describe why.

Herds and Tribes; Fields and Gardens

A thorny hedge is in some ways more inclusive than a tall tree. It will welcome voles, possums, and birds all alike. Still, it remains exclusive of some other animals: the larger grazers.

While typical Internet idioms say posts “go viral”, what I see myself is that they “get stampeded.” And to the paleolithic hunter’s instincts deep in the human unconscious, drawing a stampede to one’s site sounds amazing: literally, getting herds to stampede into natural landscape or artificially made “kite” funnels was an important human hunting strategy for thousands of years. It might be how we drove the Ice Age megafauna extinct.

Getting stampeded online can be more of a mixed blessing. It can grow a writer’s audience, but it’s not necessarily an invested audience or a healthy audience to serve. For a pure attention hunter, it’s all upside and extra sales, but for anyone who had been trying to do something else, like grow a stably differentiated community, the stampede might trample more than it gives. One of the more iconic older blogs based on an agricultural metaphor, Ribbonfarm, pivoted to a more private, less virality-friendly “cozyweb” to get away from the thundering herds.

More common idioms describe the risks of virality in different terms. When virality attracts negative attention, and the negative attention can be interpreted in fantasy tropes: purely antisocial trolls, crudely tribal orcs, or unthinking zombies. They can come in mobs or hordes. A common nature trope is the swarm of stinging bugs: “I really kicked the nest with this one.”

These have their place, but with this project I would like to have a relationship to the virality-following crowds that injects less negativity into my lifeworld when confronted with undesired attention. Rather than ravenous zombies seeking flesh or an angry swarm seeking to destroy, it could just be sheep eating all the garden flowers. They can do it without any hostility or evil at all. That’s just what the flowers are for, to the sheep. If you want to grow flowers, you have to keep them out. Blackthorn flowers are a different story — not so appetizing and not so accessible, so they can survive to become berries. When animals come for those berries, that’s how the seeds are evolved to spread.

This trope still risks pathologies of a different kind, like the infamous “sheeple” stereotypes, but since I don’t personally despise sheep or cattle, I’m not as concerned about them. There are field-like online spaces in which I enjoy being fairly sheep-like or bull-like, myself, and when I’m accidentally acting bull-like in someone’s china shop rather than in an open field, I try to take any warnings to that effect well.

A hedge doesn’t need to hurt or hate any of the big grazers to do its job of bounding them. Cattle can even enjoy a hedge’s shade.

Radicalization and Desertification

In a different time, explicitly saying all this might be an entirely superfluous exercise. People and their communities would find each other more naturally, falling into complementary matches through the unconscious genius of normalcy. But putting it flatly: that is not seen much on the Internet today.

Instead, too many of us have been radicalizing bizarrely and getting lonelier and lonelier. Too few of us have been forming good shared lifeworlds. Too many of us are instead getting locked into lazy, self-flattering conflict tropes. These framing assumptions steer even good people who would be friends in person into mutually insulting, mutually disrespectful equilibria online.

I’ve generally avoided these dynamics, leaving the public Internet to its trolls. This letter is my first public personal writing on the Internet since a small Twitter account for a couple months in 2020; I stick to groupchats as my primary social medium.

I’m here again now, but I can’t follow the prevailing patterns of lifeworld in any of the major movements I see online. I saw too much of myself in Mark Fisher when he passed in 2017, and I’ve been close with too many vets with trouble reintegrating into civilian life. I know that when shared lifeworlds aren’t coming together, trying to act cool about it or “just get along” is a mistake. Letting it go unsaid is a mistake.

All these nature metaphors can seem merely corny if you ignore the gaping pit motivating the conversation, but please don’t ignore it. These are metaphors we live by, to quote a well-known title. We also die by them. The natural symbols of the lifeworld are hard-won products of geological eons’ worth of life and death and fear and love, even and especially when they’re presented at a kids’ level. They are roots and soil.

With The Blackthorn Hedge, I’m experimenting going into public with a jargony abstract mission statement for myself: I’m trying to establish credible and loyalty-inspiring space for spontaneous conflict representation and resolution between opposing traditions of justice and rationality using a full suite of tools from reflexive sociology and the theory of communicative action for the widest possible range of age and experience levels. I don’t expect that to make much sense to many readers up front, much less make good brochure copy. Even when it does make sense it is not and should not be persuasive in itself: it could just be technocratic word salad if the terms aren’t fully and verifiably grounded in simple practices that people won’t need the words to appreciate. It’s mostly just for me, for now.

In the meantime, I hope the things I’m writing are rewarding to read for your own purposes and interesting to share with friends for your shared purposes with them. I hope the posts are all adding up to a funny sense of abstract place in the space of ideas for you, and I hope that they don’t seem too likely to spread pests. I know that for now I won’t satisfy those who would like me to join their herds on stampedes, but in time I hope even they come to appreciate this hedge, too, as a shady border that doesn’t get in the way so much as it helps keep their fields from eroding into deserts.

John- This is both entertaining and enlightening at the same time. I particularly love the bio-natural and the warfare stronghold analogies (and graphics). So stunning to have them put together in such a precise way.

Let's by all means each contribute to fields and hedges, and avoid stampedes...

Have conversations and not battlefields.